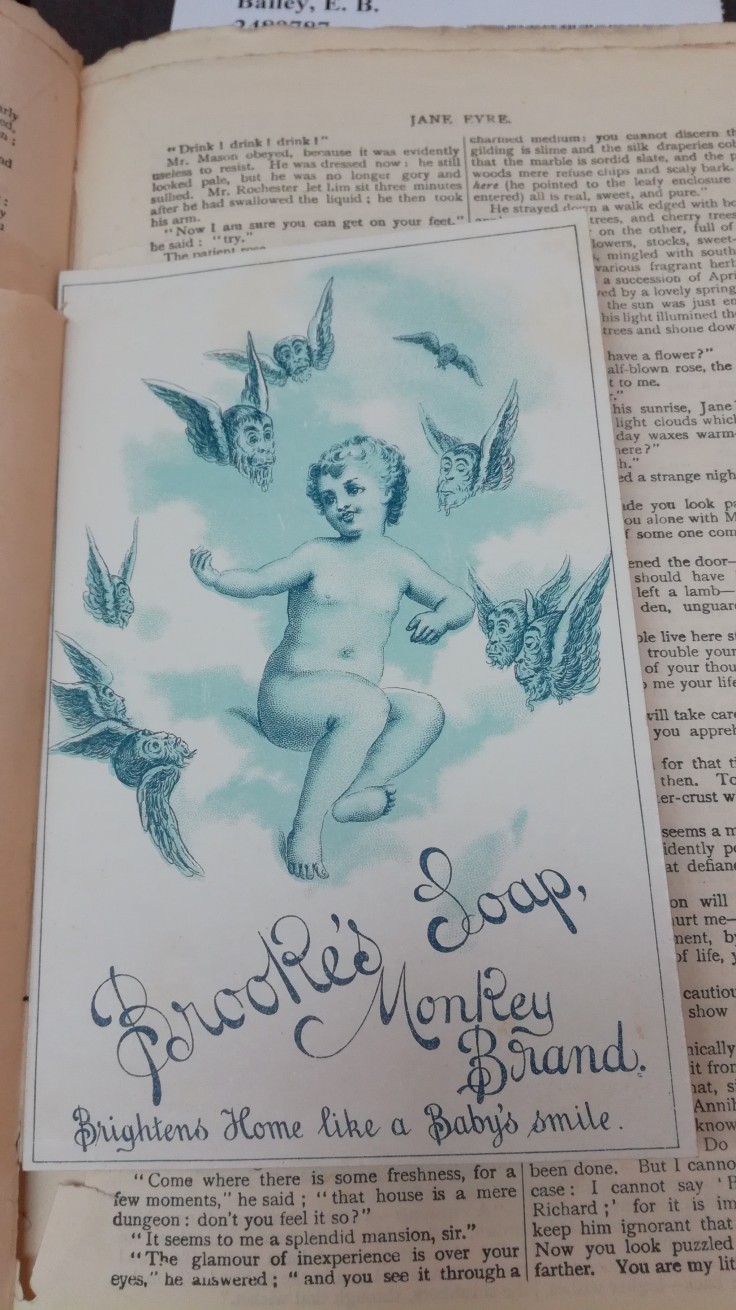

This flimsy paperback edition published by Frederick Warne in 1894 (and found in the collection of the Bodleian Library in Oxford) sees Jane Eyre squarely aimed at a readership of middle-class mothers, with the inclusion of multiple advertisements for domestic need on the inside and outside covers; a ‘nursery book’ series for ‘Young England’, ‘Mellins food to infants and invalids’, bunion removers, Pears Soap and, as an insert sewn into the middle of the book, a coloured duck egg blue, two page card advertisement for Brooke’s ‘Monkey Brand’ soap.

The opportunity to own her own copy of Jane Eyre signifies that the middle-class woman reader had some money to spend on reading and some leisure time in which to read; the thin paper quality of this particular edition, the close type and slightly larger than A5 page size, allowing the whole book to be printed in just 168 pages (keeping costs down), makes it clear that this was not a book that would have been held in an upper-class library. The only evidence of this book’s ownership history is a partially ripped off sticker on the front cover, which advertises a bookshop called ‘Grattan’, in ‘Borough’, (London?) Bridge’.

Monkey Brand soap was exceedingly popular in the late nineteenth century. Sufficiently well recognised to feature as a joke in George Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion when Henry Higgins tells his housekeeper to take Eliza Doolittle upstairs and clean her up, and to use ‘Monkey Brand, if it won’t come off any other way’. The joke was that ‘Monkey Brand’ was for cleaning objects not people, thus working-class Doolittle must be scrubbed like an object in order to fit into upper-class society. By the time of the film adaptation, My Fair Lady, in the 1960s, cultural sensitivity and presumably the fact that the product was no longer a household name saw the line changed to ‘sandpaper, if it won’t come off any other way.’

Anne McClintock in Soft-Soaping Empire[1] identifies the popular use of monkeys in advertising as ‘simian imperialism’; the use of anthropomorphised monkeys was a common trope in advertising of domestic products at the time, and from the 1860s onwards soap sales soared, due both to the increase in advertising and consumerism and also access to source products such as cheap palm oil from overseas farmed by slaves. The monkey image suggested the exotic to an audience of Victorians who would never get to see the empire first hand. Aside from the obvious racist undertones, a leaflet like this in the middle of Jane Eyre is explained thus by McClintock: ‘The appearance of monkeys in soap advertising signals a dilemma: how to represent domesticity without representing women’s work’[2]

The irony here is that a picture of an innocent, clean, naked infant surrounded by winged monkey heads (monkey angels?) is at once an aspirational picture of domestic purity and gleaming hygiene (achieved not with physical effort but rather thanks to the powerful cleaning product from distant shores) but also a gentle reminder, while the poor woman reader is curled up with her good book, that she cannot entirely forget domestic duties. The card is attached to the story in the middle of the dramatic chapter twenty, where Grace Poole/Bertha attacks Mr Mason in the middle of the night, to which blood-spattered scene Jane is alerted by the eerie screaming. The dramatic tension is rudely interrupted by a garish advertisement for soap. It is ironic that the advertisement is printed on harder wearing card than the words of the book, and in a bright colour, so that it survives in much better condition than the book itself – in fact the heavy ad card has produced a rip in the page of the book. It feels almost like an aggressive intrusion, capitalism tearing at the pages of the work of art by Charlotte Bronte. Jane Eyre was written in 1848 before the era of mass marketing, it is instructive that an edition published fifty years later communicates a changed world of commercial reality that is literally pulling at the pages of the work.

[1] Anne McClintock Soft-Soaping Empire: Commodity Racism and Imperial Advertising Routledge 1994

[2] ibid